The Red Spectacles

I don’t think an artist should have any responsibility to their audience or culture. I understand this is somewhat of a dramatic shift from the things that I have written about previously, but it has been on my mind for quite some time.

A few months ago, I saw a film titled “The Red Spectacles.” It’s by a Japanese director, Mamoru Oshii, set in the Kerberos Cop universe. This is somewhat of a deep cut for older otaku—like many Japanese intellectual properties, the media they utilize can be sprawling. Manga, radio dramas, anime, video games, and original video adaptations. Oftentimes what is or is not in-universe canon can become a contentious topic, but I don’t want to discuss any of that here. Instead, what you need to know about the Red Spectacles is that it is but a single part of this odd world that is similarly dense and impenetrable. Not that any familiarity with it is absolutely necessary.

The Red Spectacles, as far as the Kerberos Cop timeline is concerned, picks up at the tail end of a fascist Japanese government hunting down its own foot-soldiers. Although the film opens with the Kerberos unit in mechanized armor using Nazi machine guns to riddle an entire platoon of assailants with holes, you are not seated for some kind of action thriller. The reality of the film is much more bizarre.

Similar to earlier French surrealist films, it veers into bizarre territory not at all dissimilar to Luis Buñuel, just dressed down in of-the-time Japanese aesthetics. It is a bizarre, although beautifully-shot, portmanteau of noir, science fiction, and slapstick. Similar also to Luis Buñuel is that spoilers ultimately do not matter. The plot is, in a way, totally irrelevant. Whether or not this was intended also does not matter, I find the fact that it doesn’t an interesting part of the charm, considering that’s the last thing you want a canonical piece of in-universe storytelling to do. You’re not watching the Red Spectacles because of some new insight into the moral philosophy of Kerberos Cop, nor is it even really capable of delivering some shock to the psychological system that surrealist cohorts wish that it would.

Although tonally the film is an almost abject failure, it is a beautiful one. This, alone, prevents it from nearing a sort of fatal feeling of being boring. Something I deeply enjoyed about it was the usage of changing color gradings. The application of color in this film is very particular. It goes without saying that red is a very important color to not only this film but the broader whole of Kerberos Cop. What I left considering was how much is implied when a single film shifts from full color to sepia tones; how effective such a thing is, along with strong shot composition, of establishing a noir tone.

So effective that the many scenes of Jackass-style bathroom brawls, wedgies and all, felt extremely uncomfortable to sit through. At points like that, I realize that I was enjoying this movie despite itself. I have an odd appreciation for things that, intentionally or not, torture the audience.

I was seeing this film at the Metrograph in Manhattan, New York City. On paper, everything about the Metrograph is brilliant. Vintage seating, drinks available, a (from what I hear) quality restaurant on the top floor. The screening lists are curated and they’re curated quite well. Along with The Red Spectacles, another of Oshii’s OVAs was showing by the name of Angel Egg—a similarly beautiful otaku classic on gorgeous 35mm.

Were this all, the Metrograph would be great. It is better still, however. It features a bookstore with invaluable texts on film-making from top to bottom. Shot composition from different photographs, editing principles from famous editors. It also has a print magazine which, shamefully, I have not read, yet this is something that I deeply admire. They even have a streaming service which is not bad at all. I saw a silent documentary following Juggalos to the Gathering of the Juggalos which was one of the more interesting shorter films I’ve seen in quite some time.

Unfortunately, as good as the Metrograph is on paper, the Metrograph has a terrible, horrible problem: the people who go to the Metrograph.

Perhaps in my ignorance, I do not understand that people are just like this these days. In having spent a considerable amount of time watching films at this establishment recently, however, I get an odd sense of alienation from the people who sit in the same seats as I do. One such time I recall, I was seeing Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell OVA, a film I have a great fondness for as a piece of anachronistic fiction so incredibly tight that the themes are built into the animation itself. It’s not secret (at least it shouldn’t be at this point) that Major Matoko Kusanagi is very often bare-fleshed. You see her breasts. You see her butt. None of this is gratuitous, as the most important theme in this animation—a medium existing all because of the relationship between life and movement—is that there is a kernel of humanity existing in the literal flesh of someone’s body.

Yet, the sight of Matoko Kusanagi’s breasts withdraws from the audience a sort of exasperated sigh. Oh, heavens! Breasts, again!

Over the past few years, talk of film being a “dead” medium has come up time and time again. It’s dead in the traditional sense that huge studios existed underneath an economic and technological circumstance which is quickly evaporating. People blamed the VCR, then they blamed YouTube, then they blamed Twitch, then they blamed streaming, then TikTok, then AI. What I find odd is how few people consider that the same thing is happening to music at the pop culture level. Financing a band does not make sense anymore when you can keep in-house writers for a new pop star, a way more lucrative strategy than investing in a band. Or, you could give a new rapper an advance contract and effectively chain them to your label in servitude until it’s paid off, by sales or by principle.

Even to pin the blame on technological singularity, neatly represented by AI, just feels incomplete. A few months ago, my second film aired at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan. It was a short cartoon, but animated all the objects and slides myself. It was an idea which means a lot to me, and I’m grateful to have had the chance to simultaneously give it expression and accomplish a childhood dream of mine.

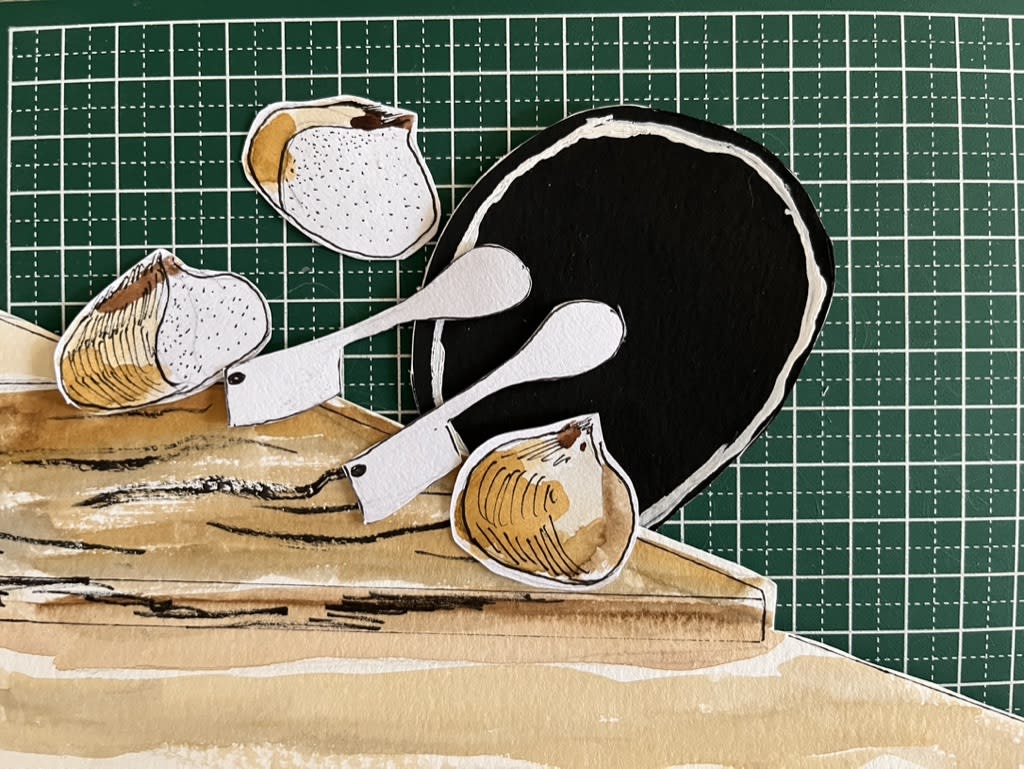

I used charcoal, gouache, ink, and watercolor. It’s largely cut-out and replacement animation, but I wanted the egg-drop scene to be very dramatic, so I opted for hand-drawn slides. I was nervous how the smear frames would pan out in motion, but I guess I’ve seen jiggly eggs drop so many times that I should have been confident.

It was shot on something called an animation stand, an Oxberry to be specific. It is an esoteric device whose name does not really reveal what to expect in operation—a downward-facing fixed focal length 16mm motion picture film camera suspended above a flat table that moves up and down on a motorized bike chain. You can take a single frame capture or hold the button down if necessary. Because of this, no real editing needs to take place—you learn that animation is almost entirely pre-production.

I do not harbor any illusions about being some up-and-coming film-maker. I have some ideas which I think are quite good along with a foundational curiosity for the objective components of the medium. I think the exposure triangle is fun to think about. I think that inventive cross-dissolves are thrilling. I think it’s imminently possible to tell a compelling story in a short amount of time without the need to seek laurels for having done so. If it entertains me, I have faith enough.

When my cartoon aired, it aired at a film festival where people were making films with different techniques and different focuses, and on different mediums. For example, a group of students were making films on super 8, a medium I have no experience with. The audio sounds very specific and the image quality on the film is very specific, too. One of the first films was about a woman who wanted to record herself pole dancing. To my horror, one of the later films was also about a different woman who wanted to record herself pole dancing. It was an incredibly uncomfortable moment, watching two independent people develop the same idea. It contained a sense of horror—that I could belabor something which is such an incredibly personal project, only to have the person two seats to my right reveal the same idea when it comes to presenting your filming plan or storyboard.

One of the reasons that I like making films is because I can think of few other methods of storytelling which are so obscured from immediate recognition by the audience. To learn how to make one, even if amateur, is demystifying a great deal about the essential component of storytelling: lying. Sometimes I wonder how many people saw In the Mood For Love and left thinking, wow, I cannot believe how gorgeous Hong Kong looks!

Because of this, however, film is sort of uniquely victim to the self-stupefying impulses of culture. As I wrote earlier, film is a difficult medium to understand objectively as a passive observer. Focal plane distortion is an incredibly complicated subject to explain even when you know what it is. Similarly, most people cannot really understand how much of nostalgia for the recent past exists because of the way Kodak film renders colors like red; how it handles flesh tones. Even the language photographers use to describe this kind of thing—”color science”—is, itself, a borrowed term obscuring what they are actually trying to communicate. In the end, a modern general audience is left incapable of understanding art, or “content” if you will, unless the “vibes” are immediately intuitive, understandable; diffusive essences all working together to provide for the viewer a quality of feeling totally divorced from the formal supply chains of what makes art… well.. art in the first place. It shifts the point of any one piece of art from being a self-contained expression to an experience for the audience to recompile into an ever-metastasizing array of vibes; you do not even need to develop language to describe it, you can just assign it a vibe.

Even though the general audience’s desire for illiteracy feels like an increasing trend, it is unfortunately not the case that the culture of a cinephile offers any kind of meaningful alternative to this. Rather, it is a ghetto of a particularly conservative disposition, something which seems to be a recurring theme of the insular world of art these days. People, despite their suggestions otherwise, do not like culture changing. RuPaul’s drag race is on season 18 after having debuted in 2009—seventeen years ago. Yet, you can find yourself at a taxidermy competition in Brooklyn and see drag queen nuns shoving crucifixes up their asses for some reason (I walked out during this). Critics, generally the corrective measure against the total onslaught of bad art, seem themselves to be ineffectual agents acting against this.

There is no structural prescription, certainly not one which can be abided now that generative AI has made the creation of art supremely democratic and accessible. It’s funny in way to think of the postmodernists made vindicated, not due to fascist takeover, but by maximized means of democratic participation in cultural production. Nor do I have any similarly romantic or heroic suggestion. In fact, if there is any prescription at all, it’s that developing taste is difficult, but perhaps never more important than it has been right now.

I don’t think that curating an audience’s sensibilities or expectation is the responsibility of an artist. Maybe in some other time it was, but the only responsibility any of us should be asking of an artist these days is to please have some taste.

A few addendums:

Firstly, I do not know what has led to the increase in people subscribing to this neglected substack. I don’t know what I want to do with it, and I cannot promise I will utilize it with any regularity. If this is due to some kind of algorithmically-defiant migration from a website, that’s fine but understand that I am not afraid to bore you.

Second, I want to discuss some plans that I have for films in the upcoming year. Soon, I will begin shooting a stop-motion animation project which I’m excited about. I don’t want to share too much too soon because these things can change during production, but I am hopeful that it will be salacious.

I also have two more film ideas I want to get out by the end of the year. I am currently looking for an actress for a film about oral fixations. If you’re in the New York City area and are interested, please send me a direct message on this website or others. I don’t care if you have acting experience.