Look Sharp!

March Requests

I was shocked to find one of my last commenters leaving a request. It might sound strange but it’s very sweet to have one at all. I did and do not consider myself an authority even in my most passionate subjects, but if I can help others learn, I would absolutely love to do so.

in light of discussions of taste, is it acceptable to request a future article on plating if it so moves you?? your food is always beautifully dished with evident care, yet my past attempts at plating (even when i try!) verge on an insult to the animals and farmers whose products i am consuming. is it a "you have it or you don't" type situation? please help!

I thought about this for some time, and it’s occurring to me that there was never any cleanly demarcated point where I realized that I learned to plate all of the sudden, or even a moment where I thought that I plated well. There is a marked difference from my earliest days making a French omelet every day until I got it right to now, where I am on the hunt for boutique ingredients and, naturally, boutique garnishes as well.

A lot goes into building a plate yes, but many of the things which I would consider to be rules (or perhaps guidelines) are natural things with perhaps a bit of finer attention to detail. For instance, no one puts gravy underneath rice; the idea is to have each grain soaked. What might be less obvious is how simple the addition of a small bowl-shaped indention into your bed of rice, made with the back of a tablespoon, can make a braised dish or saucy protein look as if it is floating neatly and impossibly.

This chicken tinga is a recipe I have known for years, I do not even recall when or where I learned it. I wanted rice and beans, that chicken tinga was made at all was incidental. I simply had all the ingredients for it on hand. I like to reduce the adobo-based sauce until it is very sticky. It is basmati on the bottom with the very same indentation I mentioned earlier, using a tablespoon. This allowed me to fill that “bowl” with black beans, such that putting chicken tinga across the top makes a modest dinner bowl seem positively full to the brim.

Of course, arrangement is not always so straight-forward. Oftentimes you do not want to rely on classical combinations of things, at least not consciously so; though those associations are there. Indeed you could design any number of pleasant-looking dishes with simple rubrics like “red meat, starch, and greens.” In these instances, most of your plating is handled by the attention to detail; the to-taste components of those dishes before they hit a bowl. Reduce your braising liquid until it is just right. Give your spinach exactly how long it takes to become just tender. Pull polenta from the heat just as it begins to leave sharp wisps as you whisk it. If you account for these factors, most of what you need to do is already safely taken care of.

Here, I braised some quality short ribs in a red wine sauce with potatoes, following the same directions I mentioned earlier with just one omission which is pertinent to bring up now. I knew in advance that I did not want kale on top of polenta, and that I did not want short ribs on top of kale. Yet, this left me with a bed of parboiled and sauteed kale. A quick glance around my kitchen revealed pearl onions which really put everything together here. What savory liquids the polenta did not soak up would pair extremely well with the satisfyingly sweet toothsomeness of caramelized balsamic onions and kale.

Something I would like to stress before continuing is that there is no rule against putting beef on top of kale. In fact, you could remove the polenta from the equation altogether and the dish would still be fantastic, arrangement would just change. In the above bowls, every element must be visible; this is the real rule which should not change. Were you to instead use a plate proper, the very bottom would be a bed of the same kale, place your short rib portions in the center, reserving your pearl onions to lay around your beefy centerpiece. I made the decision that I made, putting what, where, because after the rules and guidelines, it is once again about taste.

Lastly, when plating, uniformity helps. Use the same dinnerware for all involved if at all possible, and do your best to replicate one plate across the board. Take it one step at a time, though you should save what is the most important step for last: garnishing.

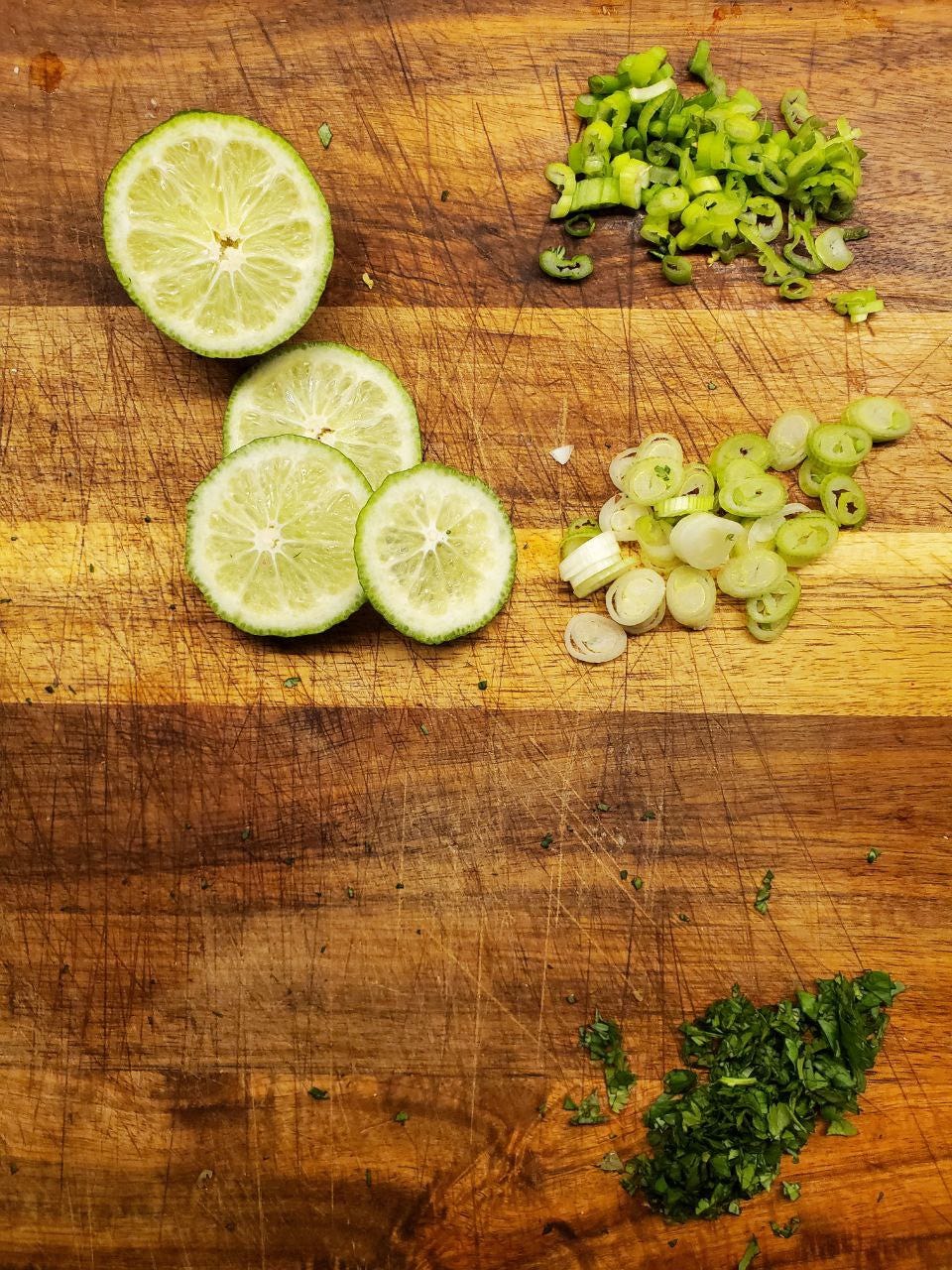

Before I continue, I want to say that you should always keep fresh herbs around. If you do not, start with either chives or Italian parsley. When you get them to your home, bundle them up comfortably in a damp paper towel and reserve them in your fridge; this will keep them crisp and fresh for a shocking amount of time. Italian parsley gets a rough chop, chives a thin slice. After cutting, pinch it as you would the collar of an intrusive kitchen mouse and raise it at least a foot above your plate before sprinkling haphazardly. Do not attempt to meticulously place leaves, this always leaves things looking worse.

With that out of the way, I want to say that garnishing is still much more than simple window dressing. Few things, even desserts, benefit nothing from an herbaceous garnish, but for many cuisines, different garnishes highlight a unique character.

Duck fesenjan is a Persian dish, a stew of chicken legs in a broth that contains both pomegranate molasses as well as walnuts. I’ve tasted few things like it, a truly remarkable profile born from the earthly stock that would have only come from Persia. What better way to highlight such features than to include them in that very garnish! Toasted and roughly chopped walnuts with pomegranate arils, both easy tasks to fit in the long cook-time for both duck fesenjan and the steamed rice and tahdig.

In other instances, a garnish is so important that a dish is simply lost without it.

This caramelized onion soup had a Spanish flavor profile with tomatoes and pimenton, all placed atop croutons. Were I to just add parsley and perhaps a bit of olive oil, the finish would have still been drab. The soup was made with caramelized onions and tomatoes, much too thick for olive oil to show any kind of helpful contrast against the rest of the dish. In instances like this, a poached egg is not only the perfect garnish, but the perfect addition which makes the whole dish work. The pillow-y soft whites provide a nice color and textural contrast, and the golden yolk spilling out is likewise sharp and provocative. Without this very garnish, it would simply be a side dish of no remarkable character at all.

Now that I have hopefully illustrated the process that I use, I want to reassert that I do not think it is a matter of having it or not. I think it is natural to study things that you love, to really consider the subdued contours which perhaps others would overlook. Maybe it is your favorite musician, maybe a painter. Maybe it is someone you love, when you notice things about them that perhaps they might not even be aware of, but for you it becomes a new element to know and appreciate where perhaps no one else did before. Here it is no different. I would be so bold in fact as to say that looking at things is, in and of itself, a skill; and that you should simply look at things often with the intent to consider them.

Values, hues, contrasts, lighting, everything that you look at interacts with these concepts, whether it is a picture, a plate, or a person. What I want is what I would consider the only applicable use of the word “handsome”; something dignified, pleasant, and, hopefully, charming.

actually to be honest if you wanted to write something on "communicating with food" I would read that. Just about how and why you would serve dishes to family, friends, 1-1 dinner, to a partner, a prospective partner, etc. Enemy, even. why not

When I moved to New York City, I found myself picking fights time and time again by insisting that humans are not verbal creatures, that language is a compromise we make when it is more important to agree than to be recognized. Not to beleaguer agreement because we obviously need to agree on a lot. We need to agree on what “cold” means because it’s possible to “feel” so “cold” that you “die,” and that last bit is especially important for us to agree about.

Yet, even considering mortality, this is one of the earliest themes in the winding maze-like alleys of human cognition. Its symbolic and psychological baggage is primordial, extending so far that our very language has, in contrast, straightened out like a neat series of roads in service of, at least in part, preventing the reality of death in the formation of clinical, objective linguistic developments of medicine, anatomy, physiology, and even nutrition.

Same as then, I am willing to accept that I might be projecting, that maybe others can express themselves with words while I simply cannot, not in any meaningful way that satisfies me. Rather than attempt to address this with words, I want to offer brief illustrations which I think would better serve both of us.

One of the first people I had the pleasure of meeting upon moving to New Jersey was an Azerbaijani woman. A remarkably sweet and intelligent woman as well as a gifted composer, and I was so thankful for her hospitality months ago that I resolved to do something for her in return, however cryptic.

Azerbaijan as a country borders Eastern Europe and Western Asia, because of this there is a unique culinary confluence of traditions. Of Eastern Europe I know sparingly little and of Western Asia I know less, but I wanted to make her in particular an Eastern European pan fried cheesecake known as Syrniki. It took practicing, as it involves an ingredient which is somewhat rare to the United States: farmer’s cheese. Once its rarity is adjusted for, then you have to adjust for the moisture content as no two cheese manufacturers produce the same cheese. It took studying, adjusting ratios, nailing down the gramage of what “half of a large egg white” means in workable, repeatable terms.

After working that out, I invited her over for a brunch experiment I wrote of previously as I felt like such an event should be at least this attentive of the parties involved. After all, part of hosting a brunch or dinner is the desire that your friends lavishly enjoy themselves, and part of enjoying yourself is having who you are recognized in some way which should be meaningful. I wanted to say a bit of thanks in a way that didn’t require such limp diction in contrast.

The only instance where this does not hold true I would say is feeding an enemy. I have not had this experience too many times in my life, but I can think of few worse things to do to a quality rival than impress them.

i never thought i’d ask for a lyrical essay, but here i am asking for a lyrical essay on what it’s like to bite into a piece of bread with butter on it

I did not want to cook this morning. So I did what I always do when I don’t want to cook. A cast iron skillet on medium heat, butter pop-flying out of my hand and belly flopping into the pan with a satisfying thud. I watch it melt because it’s peaceful.

Cutting slices from the baguettes I made explodes crumbs all over my kitchen. Yes, the baguettes looked a bit too much like yams, but you can’t argue with sound. I fit them into the pan and set out a pat of salted butter from the fridge near to it, to soften. Three eggs crack open into a bowl with a bit of salt, white pepper, and water. A thimbleful of water, to be inexact.

Once the baguettes finish toasting, the eggs go into the same pan. They seize and curdle and bellow. You’re not supposed to make a French omelet in a cast iron skillet for a host of reasons but I’m not actually cooking. If I were cooking there would be hash browns, muslin towels, flour, dry aging, parboiling, blanching, emulsifying; I’m just shaking a pan—a heavier one than usual—then gingerly flipping the omelet in on itself before the dismount. It’s important to get it right, yes, but even if you get it wrong, scrambled eggs are perfectly edible too.

Of course it dismounts right on to the plate near the toasted baguettes. There’s not a lot of time to appreciate it, though I wish there was; it’s like a palate of colors chosen for a canvas. Yellows, darkened by reds for the perfect golden brown, a hint of indigo to dramatically increase value around the darkened edges of the toast. I’m sure that’s what a painter would choose, I think, knifing through the salted butter and raking it across the toast. What the hell, a bit of butter on the omelet would give it a nice gloss too.

A fork cuts right through the omelet as if it were also butter, and does a marvelous job of spreading it across toast too. It’s a plate of pauper ingredients, pennies on the dollar. It might take skill, not that I have used any of it. A clockwork affair that required no agency, a breakfast Rube Goldberg machine. I could make any number of lavish breakfasts, in fact it’s secretly my favorite meal to devise. Yet nothing redeems its modesty so violently as when that first bite of toast crunches between my jaws.

Eggs, flour, salt, pepper, water, and butter. These ingredients are the basis of meringues, of pasta doughs; of dumplings from as far east as China and west as Britain, Italy, and France. So universal as to be mundane, yet it is anything but. Rather than hours, it is minutes; there is in fact nothing modest about it at all. It is unassuming when blessings are not counted, when you do not acknowledge the miracles that you have. It is humble only when the idea of what things should be occludes how compelling things actually are.

I have made macarons and galette des rois, all immensely satisfying things to pull from an oven and seat on to a cake stand. Yet, sweet as they are, nothing fills me with love for the world and adoration for the pleasures of the flesh more than the sweet taste of bread and honey.

thank you for your measured response! you have given me much food for thought, my eggs and greens this morning already looked a little more dignified after reading this.